You should feel small, because you are. You are the dearly beloved of the Creator of the universe, made in His image. He sacrificed Himself for you, out of intense love for you on a scale unimaginable to you. You matter. And yet, you are naught but a human: you are naught but small.

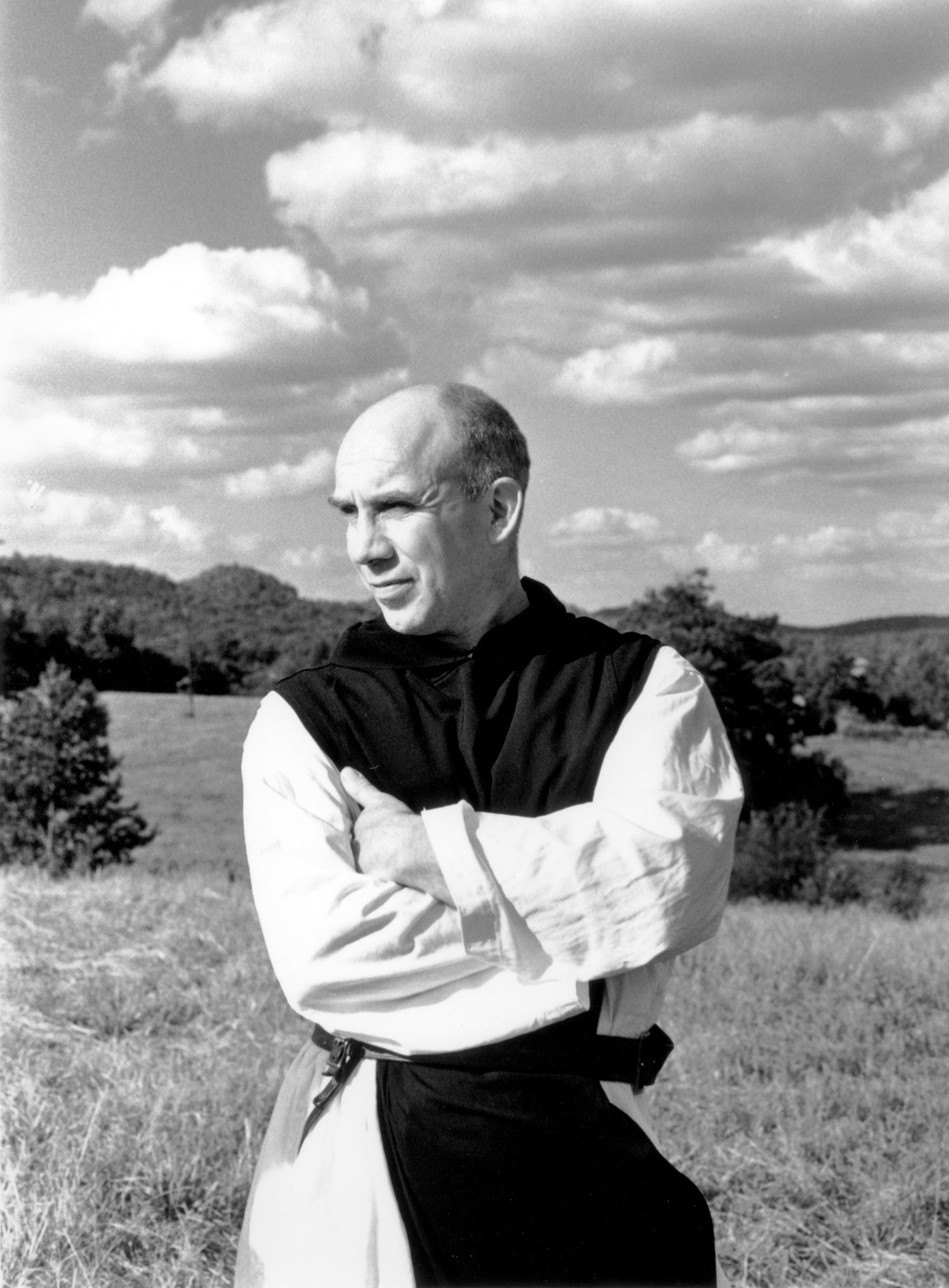

I just finished reading The Seven Storey Mountain by Thomas Merton. While it was a very impactful read that everybody stands to benefit from, I do not recommend everyone to run to the store and buy a copy. A bit of perspective (and a few caveats) are necessary to understand Merton and his life. The Seven Storey Mountain is an autobiography written when Merton was only thirty-three years old. He was very young, still reeling from the impacts of the things he writes about, with a limited perspective on how they would change the story of his life to the end. That is not a criticism – indeed, I believe it is one of the unique things about the book that give it its impact.

This is the story of his conversion from a casual and disinterested atheist to a Trappist monk. Truly a huge leap to make within only thirty-three years, he walks the reader through each step. His narration of events is peppered with essays of contemplation. The essays vary widely; some are reflective, some theological, some accusatory, and some are simply tangents in which he praises God before coming back to his own story. This gives the novel a unique flow that I found captivating. Despite the fact that I knew the story’s end (he becomes a Trappist monk) I still found it unpredictable, never knowing what the next page would bring.

Reading this directly after Dante’s Divine Comedy was an excellent choice on my part. Not only did Merton name his novel after the seven levels of Purgatory as described by Dante, but he expresses a fervor for uniting as closely to God as possible that is reminiscent of Dante’s time in Paradiso. In the epilogue of this autobiography, in which Merton contemplates contemplation, he describes in detail the need we all have for a deep interior life. He presents the following paradox of the Christian life:

“We cannot arrive at the perfect possession of God in this life, and that is why we are always travelling and in darkness. But we already possess Him by grace, and therefore in that sense we have arrived and are dwelling in the light.

This sentiment is not easily grasped, because it is truly one of the mysteries of the faith. Due to Christ’s sacrifice and the grace God affords us, we have the opportunity to find our way to heaven, to unite with Christ. The way is long, however, and often quite murky. He iterates it again like this:

“But oh! How far have I to go to find You in Whom I have already arrived!”

In living a Christian life we acknowledge His presence within us while also acknowledging the distance of heaven. This distance is vast, and our small, slow legs can only hope to keep on the path next to Christ as we traverse through our sin and shame: that is our only hope of crossing it.

This paradox, made possible only by the unfathomable love of Christ, floors Merton, and it floored me as I myself read. Our Father pours so much love into me; he created me with love and He died for me out of love and he continuously forgives me for the sins I continue to commit out of nothing else but love. And yet I am made from dust, and to dust I shall return.

Even as Jesus was nailed to the cross on which His people crucified Him, He pleaded:

And Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.” Luke 23:34

We know not what we do. We know not how incredibly small we are. We know not the lengths Christ must go to bring us back home.

Merton doesn’t come to these conclusions until the epilogue of the novel. It isn’t until he is already a monk that he understands the interior life we all must have in order to begin fathoming these core truths of our faith.

His conversion began when he first truly encountered Catholicism. There was something about the Catholic church that pulled him into it; it was a discovery that changed his life. One of the first descriptions Merton gives us of a Catholic church comes from his friend Bramachari, an Eastern monk who travelled to the United States. Bramachari’s impression of the Catholic church was in stark contrast to the Protestant churches he had visited since he came to America: :

“These were the only ones in which he really felt that people were praying. It was only there that religion seemed to have achieved any degree of vitality … the love of God seemed to be a matter of real concern, something that struck deep in their natures, not merely a pious speculation and sentiment.”

Merton’s friend makes an interesting observation here, one that speaks to a very divisive issue in our current culture right now. These words evoke images of grand alters, intricate stained glass, and giant crucifixes that force the reality of Christ to stare into your soul. Chilling Gregorian chant, booming organs, ancient Latin text praising our God, effortful vestments worn by priests as they conduct mass, and especially the postures of the people in attendance: the pews full of people kneeling as the speaks the words of Christ, the movement from sitting to standing as the gospel is read, and even the genuflecting done before sitting down at the beginning of the mass. It makes me wonder how I had ever settled for anything less than this.

Merton never did settle for anything less than that. It was only the grand shrine to our Lord, that the Church is, that stirred Merton’s heart. When Merton went to mass for the first time, he felt upon entering that the attendees were “more conscious of God than of one another”. After hearing the sermon, when the time for the Eucharist began, “it all became completely mysterious.” He had been fine up until that moment, but all of a sudden he felt the horrific need to leave right then and there, during the most important part of the mass.

“I suppose I was responding to a kind of liturgical instinct that told me I did not belong there for the celebration of the Mysteries as such. I had no idea what took place in them: but the fact was that Christ, God, would be visibly present in the alter … Although He was there, yes, for love of me: yet He was there in His power and His might, and what was I?”

Yes; what was I?

After my conversion to Christianity, the It was too much. It was too scary and unwelcoming, and surely not what Jesus called us to. It made me feel small in an uncomfortable way. So I settled into a non-denominational, comfortable church; sometimes the sermons were challenging, but the coffee and chit-chat and comfortable chairs and pop songs were easy. I could wander in, unconscious of my posture, without a mind necessarily turned toward prayer.

And He does; He desires to know us, and He wants us to know Him. But He also calls us to a radical life of difficult sacrifice, of leaving behind our comforts to walk with Him wherever He goes. We can’t keep forgetting that. We can’t know Him if we don’t respect all that He is. In the presence of the grand Lord and King, we are so powerfully and unimaginably small. Once we recognize that He is truly before us, we have no choice but to kneel. We kneel because, like John the Baptist himself proclaims, we are not worthy to even untie His sandals.

And thus, after that liturgical instinct that told Him the place He had entered was a holy place, he began to realize how much more his life should be. He recognized the need to strive for holiness. He becomes Catholic, and then quickly finds his vocation, his calling, as a monk. His path is interesting: at first he tries to become a Franciscan, specifically, but is dissuaded from doing so. He is devastated when they use his past against him and bar him from entering the order. He then begins to believe he has no vocation, and His faith starts to feel aimless; he is too distracted by the world around him to feel settled. After a retreat to a Trappist monastery, however, he can once again no longer shake the fact that he is called to be a monk and sets himself back on the path to becoming one.

The way he describes this part of his life is, by far, the part of the novel that makes the biggest punches. His desire for the monastery comes from a desire to rid himself of all worldly distractions. As he leaves the monastery after his first retreat he says:

“And how strange it was to see people walking around as if they had something important to do, running after busses, reading the newspapers, lighting cigarettes. How futile all their haste and anxiety seemed.”

To him, the monastery is freeing:

“So Brother Matthew locked the gate behind me and I was enclosed in the four walls of my new freedom.”

Freed from the world’s distractions and free to spend all of his days solely focused on God. Free to be small, without the world trying to make him feel big and important and lavish and in control of himself.

I mentioned earlier that his epilogue is a contemplation on the concept of contemplation. He decides that every individual is called to a deep interior life, regardless of how easy it comes to any individual person. We are all called to contemplate just how Big our God is. And we cannot do that until we understand how small we are.

What had I shed? Where was the space in my life for God? Nothing I ever did, even entering a monastery, would leave Him enough room.

Because there isn’t enough room inside of me, even if I were to empty out everything else. Because He is so big. And I am so, so small.