I am apparently not alone when it comes to taste in contemporary Star Wars content, and I took a delayed approach when it came to watching one of the recent mini-series: Andor. We had all seen just how well mini-series were doing on Disney+, and when they came out with a back story…for a back story…none of us were seemingly convinced. I for one, care almost nothing about the upcoming series based on Echo – Maya Lopez, a character we were briefly introduced to in the Hawkeye mini-series. But that is a tangent. The more pressing matter I wished to write about are some thoughts that occurred to me after watching Andor.

Star Wars has been around now for a long time, and ideas about what Palpatine’s Empire means, what it does, and why we hate it have similarly been part of general public discourse for a long time. So even if you haven’t seen Andor you can at least understand the principles put forward here.

As I was recently watching the series I realized that Palpatine’s Empire and the United States’ public education system share at least one major trait: the belief that prosperity and success comes through more control. It’s easy for us watching Star Wars to dismiss the Empire as the bad guy and to think that since they are so obviously evil none of us would ever agree with them in real life, but the entire point of Andor is to show the larger scope of the consequences of the politics of the Empire, and the sincere hearts of those who fight and think for the Empire as much as those who rebel against it.

Throughout the series, it is demonstrated that the Empire does and must exert control over individuals and systems if for no other reason than the control itself. It has, other than Palpatine’s wicked desire for total power (which I have ideas about, but I’ll leave that for later), a sincere desire for peace and stability, but the way it achieves it is through controlling for wild cards and anomalies that fall outside of its desires. It does not view its own violent actions as counter productive or destabilizing because of pride and especially because of the belief that it is the ultimate good for the galaxy. Darth Vader’s conversion to the dark side is not one devoid of logic, focusing only on the death of Padmé; throughout the prequels we see distaste from Anakin about how the Jedi react to certain injustices, and Anakin wants to change that so that instead of resulting consequences like Padmé or his mother’s death, more good might come out in the galaxy on the whole.

Public education in the U.S. adopts a remarkably similar approach to promoting success and managing students. No, the Secretary of Education does not wield a red colored light saber, but if we look at what districts and states are doing and if we look at what professors in colleges are researching and teaching to the next generations of educators and administrators, we see where the comparison is strong. Most strategies for educational systems in the U.S. revolve around this idea: controlling any and all outside factors so that students achieve academic and social success. Isn’t that a good thing? Isn’t that what everyone wants? Certainly you don’t have the know-how or ability to do the job…you just ought to let them figure that out for you.

There are so many things that trouble modern public education, and the troubles seem to have no end. Random public attacks, high numbers of mental health cases, low test scores, truancy, apathy…the list goes on. Notice, however, what the response is to these issues: more. More security personnel, more psychiatric personnel, more teacher duties, more district policies, more funding consequences for districts, more testing, more school days, more classes, more teacher requirements, more initiatives, etc. The list goes on. By overtly controlling more factors, success can still be guaranteed or even improved.

From my perspective in the classroom I understand the appeal for this method of improving school; I am constantly tired by the way I have to work against the flow of student behavior. From my limited perspective, more control seems fine because maybe it means less for me to have to deal with on a daily basis. Yet also from my perspective in the classroom I can see that something is wrong and that things each year are not getting better but worse.

The answer, like the rebels demonstrate, is less. Less control and more freedom is what is needed in school. Less initiatives, less programs, less interventions, less requirements. Notice I’m not saying different, or smaller…I’m saying less, as in take them away. Forget them. This answer is so counter intuitive because it seems bad for two reasons. One, it doesn’t answer our contemporary woes with an actionable response, and two, it seems as the responder has no care for the fallout of such a solution. Yet both of these, in our contemporary context, are not true. Just recently my wife showed me a social media phenomenon of people talking about “Silent Walks,” where Gen Z somehow believes that they have come up with the idea of a long walk outside without the influence of technology. What the Gen Zers were amazed to discover was that after a while, they found their anxieties calmed; as if the constant attack of technology and busyness couldn’t somehow be the very cause of it all. The surprising answer to everyday modern anxiety? Less.

The second issue I mentioned, where the responder with such a solution of “less” seems to not care about the fallout, is the more significant objection. This is the case because it gets to the heart of the proponents of modern education. It is sincerely believed that “more” must be the answer because it is the conscientious and kind answer. It is a philosophically positive position, meaning it is a solution that introduces an intervention. The problem here is that while the motivation is kindness, the subjects of the many interventions are essentially being killed with kindness. There is simply too much happening to be effective. Think of an artist mixing colors, only to add an excess of variety to find an awful and disgusting brown as the result.

It must be acknowledged, then, that a solution of “less” will be met with inherent anger. How, the Empire asks, can we have more ‘order and peace’ if there are no interventions to establish it? Answer: we won’t. How, the Dept. of Education asks, can we have a higher rate of graduation, better student mental health, better test scores, more security, more literacy, more numeracy, higher college admission rates, less child abuse (etc, you get my point) without more interventions to establish them? Answer: we won’t. In the course of the events of Andor, the main character has just finished a heist job. Away from everyone else and after already losing several other teammates, his teammate suggests that they both split the heist and run away with the spoils. The teammate would abandon the remaining living teammates and steal the money not just from the Empire but also from the rebellion. At yet a later point in the show, a background rebellion organizer is speaking to an independent rebel faction, and is trying to convince them to cooperate with other factions, only to hear the objection that each faction had its own political ideology and can never possibly unite.

The point there is that when you advocate for “less” you are deliberately opening the door to suffering, moral inadequacy, and failures. You are literally inviting these things into existence whereas they may have not been seen before. The truth is, however, that even though they weren’t seen before, hearts were already set on them. Explicit interventions in a system the size of U.S. public education do not address problems – they cover up symptoms. In Andor, an Empire investigator is looking into missing technology. As part of her investigations she noted that fear of being reprimanded for losing equipment contributed to inferiors lying about it and covering it up. A solution to that is never addressed – but can we acknowledge that staying the course of fear tactics in a hierarchy is not going to solve the heart of the issue? The failure already existed – pulling back whatever “interventions” were already in place was simply exposing them.

Furthermore we must acknowledge that sincere proponents of Palpatine’s Empire, like Darth Vader, are seeking a utopia. Many contemporary progressivists are similarly desirous of a utopia. “With enough progress [interventions] we can achieve utopia.” As a Catholic, yea as a Christian, I strongly object to the feasability of utopia. Believing in such a utopia denies truths about our world and our existence that are unavoidably true. Free will – the ability to choose good as much as evil, is inherently part of our world. We cannot change that. Utopia inherently denies free will, since a utopic world cannot allow the possibility that someone might choose against it. Our education system inherently denies free will – of the parent and of the child. Our public education system, like the empire, cannot tolerate dissent. Worse yet is that even those who venture “dissent” still imbibe the same philosophical principles and educational practices, upholding public education as some sort of standard. In Andor the first governing authority we meet is not the Empire itself, but an affiliate authority who practices the same governance. It is not the Empire, but it might as well be. If other education systems are subject to similar regulation as public schools, like most diocesan schools, then even if they are allowed to do something like teach religion they commit the same flaws.

A world that involves free will is one that must accept “no” as a potential answer. At what point does public education accept “no” as a possibility? At what point did the Empire accept “no?” God Himself created us with free will, creating us knowing that someone would deny Him, so that those who accepted Him and loved Him did so with sincerity and not out of compliance. Just because something is good: order, peace, education, love; it does not follow that it should be forced because then it is no longer good.

What does “less” look like, then, for public education? The answer is astonishingly simple: abolish truancy and school attendance laws. While still providing the public with accessible education, but removing compliance, it means that the public chooses education as desired. Most of the ills that plague modern education would disappear, and nowhere more in particular than high school.

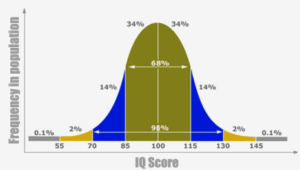

Now I find myself having difficulty suggesting that K-8 education should not be compulsory, since the benefits of a literate society are clear; but arguably it is even more critical for the K-8 sphere to be rid of compulsory education because of the demand such a freedom would put on parents. At the very least a freedom of choice for parents on what K-8 education looks like for their child should be provided.

I will focus, at least for now, on the more palatable suggestion that high school should be the first target of eliminated attendance laws. Maria Montessori, for those who sincerely follow her principles and design, does not have any programmatic guidelines for adolescents (those in the high school range):

“The essential reform is this: to put the adolescent on the road to achieving economic independence . We might call it a “school of experience in the elements of social life”

“Therefore work on the land is an introduction both to nature and to civilization and gives a limitless field for scientific and historic studies. If the produce can be used commercially this brings in the fundamental mechanism of society, that of production and exchange, on which economic life is based. This means that there is an opportunity to learn both academically and through actual experience what are the elements of social life. We have called these children the “Erdkinder” because they are learning about civilization through its origin in agriculture. They are the “land-children.””

(Montessori, From Childhood to Adolescence)

The adolescent is not primed for high school. The adolescent is ready to begin learning about entering the adult world. Sitting in a compulsory class setting for the majority of their waking hours is a living hell. Their bodies and mind are going through such a tumultuous change that asking them to sit still and comply with endless amounts of rules and requirements to endure specifically intellectual academics is crushing them. Once they are developmentally calmed down again they will be ready to do more calm and intellectual activities, and here we can talk about university, but until then it has to be a matter of choice and awareness around the unique traits of each child.

What we can talk about, then, are other kinds of activities like apprenticeships and a Montessori style farm that might actually benefit the development of adolescents instead of something like current public education.

In any case, this all begins with a discussion of removing attendance laws. The solution, as I said, is astonishingly simple. Our society has sowed a disaster, but has been covering it up for a long time; a terrible harvest awaits us on the other side. Past the other side, however, is a place of sincere growth and a beauty. We have to learn the lessons set forth in a fictional way about the Empire, and avoid furthering ideas of intolerable hyper-control. Instead of creating conditions that precipitate rebellion, we should foster environments of true growth and nurturing. By accepting that we cannot control everything and thereby create a Utopia, we find those who willingly want to create a better world and work for it. The society as a whole is actually more motivated to work towards the good. But as long as we’re forced to go to K-12 education…we will see a decline in its value.