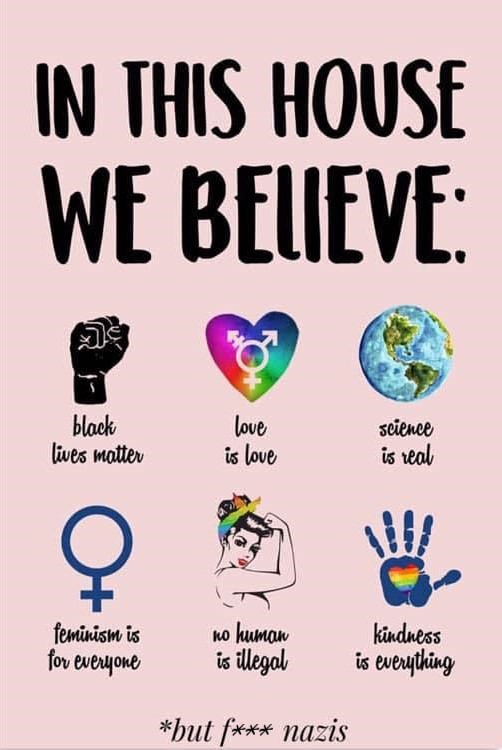

Postmodernism, the umbrella term for today’s most prevailing philosophical thought, covers a wide range of topics. Previously I have even shared a picture I found which I dubbed ‘The Postmodern Creed’:

Like any creed, there are mountains of literature that could be written on elaborating the various points, most specifically targeting how you arrive very squarely at the summative points of the creed, but also like any creed there are some core underlying currents of thought that propel the philosophy or belief forward.

One of the core notions of Postmodernism is the idea of deconstruction. Our society is currently facing this tenet of Postmodern belief with unbelievable force, as those who are in a position of power and privilege (white people) are being asked to recognize mountains of implicit biases against those who are oppressed (black people), and, most importantly, are being asked to remove systemic issues that enforce such a divide between the powerful and oppressed. What is interesting about the idea of deconstruction is ultimately that postmodernists aren’t trying to tell white people that they are literal racists (although there are plenty of explicitly racist people and they are saying that, too), but that the systems of societal structure and thought into which we are all born have shaped us to believe these things. In some ways we are all slaves to the systems that we are born into. So even if we do not intentionally hold racist beliefs or actively try to make a systemic gap between white and black people, our passive existence in a society that does therefore means that we are complicit with racism and are allowing it to exist.

A core understanding of deconstruction is that any formation of society relies on social constructs of some kind. Social constructs can be any formation of spoken or unspoken law that dictates some element of reality (black people are genetically inferior, poor people should stay poor, marriage is solely between a man and woman). Postmodernism holds that all of these social constructs are artificially put in place by man at some point in history and have no ground in a deeper reality than man’s own desire for power over others.

Whatever you may say or think about this way of thinking (for it or against it), it has a lot of merit in helping us realize that what we believe matters. Whatever you think about reality affects all of your decisions, explicitly or implicitly. Psychology has demonstrated that the brain makes sensory ‘leaps’ when observing and helping us interpret reality. We cannot possibly think about everything that we sense (that bell ringing in the background, the feel of your phone in your hand, the two people talking with you, how one of them smells, the coffee that’s being made behind you, whatever your toes are feeling, the AC running in the background, etc). So the brain makes shortcuts and only focuses on some of those things as relevant. This shapes what we think because we do not think or make decisions without some biases (focusing on the coffee instead of the sound of the bell). There is, though, a good chance that the kind of person you are or the philosophy that shapes the framework of your thought is going to modify what you pay attention to and think about. So even if you don’t explicitly think about how you feel about a person of a different skin color, there is a good chance (in the U.S. in the modern time) you have some bias about it. Whatever systems of thought have formed you will affect how you operate at every level (implicitly or explicitly).

There are many things that true adherents of Postmodernism want people to call into question and to deconstruct within themselves and in society as a whole. We could really spend a long time talking about all of them: economy (financial disparity), education (enslaving to old systems of thought rather than liberating from them), religion (disguised oppression), etc. But there is one thing that I want to focus on, as it actually serves to highlight a core issue in the larger field of Postmodern thought:

Sex.

Now, the truth here is that as Postmodern thought is growing in popularity, it’s seeing some growing pains. Not everyone is of the same opinion on this subject, but there are some basic agreements. Firstly, and most importantly, is that centuries (millennia) of thought have informed and told us (humanity) that sex equals 1 man and 1 woman, with the inevitability of children. This system of thought about human sexuality has been, as you may guess, oppressive. When adhering to this system of thought, there are consequences, such as the oppression of women where they are not allowed to work outside of the house or make authoritative changes in their own lives. Without any birth control, women would have to have many children, they wouldn’t be able to get higher education or a high paying career, and so they are subjugated to men who do have access to these things. Furthermore both women and men in a society that enforces such a relationship (implicitly or explicitly) are not truly free to decide how their sexuality and gender may express itself. Maybe someone doesn’t want to have a sexual relationship with someone of the opposite sex. Maybe they like both. Maybe they feel like they were born the wrong sex? Maybe they just aren’t interested in engaging in it at all? Maybe they think there is no binary of sexual identities?

The main point is that what needs to happen in every person and at the societal (and therefore systemic) level, is deconstruction. We have to all throw off these old shackles that are holding us back from being truly free to choose. As long as we are stuck in old ways of thinking, as long as we are relying on tradition and especially western colonial thinking (residual culture and thought from Colonizing Europeans), then we are enslaved to that singular mindset. Postmoderns are very interested in attempting to unveil cultural views from non-western groups of people to show that the western way of viewing sex or any other constructed system is not the only way, and that it is not arbitrarily more correct than any other.

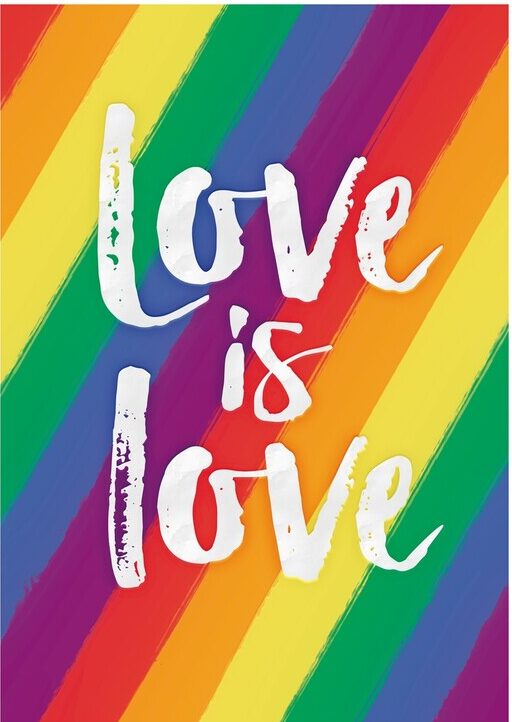

You might think that Postmodern thought is purely destructive in this manner, and that there are no positive contributions to the discussion, but this wouldn’t be true. Ultimately Postmoderns (politically liberal or conservative) are interested in freedom of choice, and then love.

Love is love is love.

Once somebody makes a choice, love them! That choice, for all you know, is exactly right for them. Don’t judge them. Don’t oppress them with whatever system of thought oppresses you. Don’t obligate someone else to conform to your view. Love is almost single-handedly the antidote to oppression, as love allows the other person to make choices free of any such oppression. If the problem at hand is being trapped by old systems and not being free to choose how you live your life, then loving people, who make choices you think are weird or morally unsound, is the answer. Love empowers people to be free and and to shed an oppressive past.

Mind you this doesn’t mean open relativism, where everyone has an inherently different worldview and there is no founding truth. A Postmodern does not truly think that murder or stealing is okay, even if the murderer or thief thinks it is the “right choice for them.” There is an inherent ground of good and evil, a necessary and basic social construction; good lying with liberation and love, evil lying with oppression and hate. Someone murdering someone else is hateful and oppressive.

This month is pride month.

This month and this time of year this oppressed group of people gets a platform to express themselves, and the rest of the world outside of the LGBTQ+ community has the opportunity to respond. Do they respond with oppression and hate? Or do they respond with love and welcoming arms?

But…what is love?

Love is love is…love? Where does this talk take us? Certainly they do not mean a romantic love, as no one is insinuating that that Bill Gates needs to develop a romantic love for every single person in the LGBTQ+ community in order to be good towards them. Some people in this community even define themselves as aromantic, meaning that they have sexual attractions but explicitly do not have any romantic attractions.

We could go through a list of multiple kinds of loves, but we don’t have to go very far to demonstrate that the LGBTQ+ community is describing a more ethereal love. But it still seems to lack a defining feature. What does this love look like?

On the one hand, it has unique expression in every relationship or case. Maybe it looks like a heteronormative (1 man+1 woman) relationship. Maybe it looks like two men who have no formally contracted relationship. Maybe it looks like a relationship between someone who identifies as a woman and someone who identifies as a man, even though appearances suggest something else. In any case, these individuals may have genuine love for each other, so it exists at a unique level, but is still more abstract.

I would suggest that there are two forms of love that exist ethereally behind the idea of generic Postmodern love.

One idea is delight. Delight is a form of love that gives one those fluttery feelings. It moves one in the direction of something (abstractly or physically) because it makes one feel good. It gives one pleasure to think, to interact, and to just exist in proximity to something or someone else. This is where we see love as feeling. Wherever one finds delight, romantically, sexually, or generally, then they are encouraged to seek it out and to live as approximately to it as possible, because having these positive feelings is exactly the kind of happiness one can get in life.

A second idea is affirmation. This is probably the most important one for the Postmodern philosophy. Affirmation is not based in feelings. Affirmation is rooted in the higher philosophical truth of Postmodernism that is essentially the opposite of oppression. Instead of someone choosing to oppress an individual in the LGBTQ+, the opposite motion is to affirm them. Not only do you validate their position and identity, but you affirm them and tell them that it is good, and that they should pursue it and pursue what makes them happy. You support them in their diversity. It is contrary to affirmation that we find the idea of hate. To not support and affirm someone is to condemn them and say that they are wrong, which is inherently hateful.

Okay…great…so what?

Postmoderns’ relationship to the idea of love is flawed. It misses the mark. It falls short.

Delight is good, but it is fleeting. If a parent bases the love for their child in delight, then both parent and child are bound to suffer infinitely. Children do not yet understand the world. They are selfish. They don’t know any better. They have to grow and have to learn about other people around them, which is the root work of parenthood. But this root work is anything but delightful. It is tough and gritty, and involves a lot of tears. It leads to delight (uhm, hello, baby giggles? omg so great), but delight is a bonus, not the root location of relationship. If you only seek out delight in a relationship, but avoid the difficult and gritty work of growth in relationship, then you are looking at a poisonous and dishonest relationship. Resentment, conflict and pain will be the fruits instead of happiness and growth. If you teach a child that relationships (romantic, sexual, or whichever otherwise) are about being happy with other people and that true relationships never really have conflict, then that poor child will have a frightful life, filled with anxiety and doubt.

Affirmation, as an ultimate level and distinction of a type of love, is poisonous in and of itself as well. Affirming someone can be good, as affirmation is fuel. It gives someone else the power to move forward and to confidently make choices. Affirmation is a necessary ingredient for growth, because how else will someone know that they can and should keep going? Affirmation is necessarily communal. One can push ahead on their own towards what they believe is good, but being alone is difficult and depressing. Receiving affirmation tells you that what you are doing is worth the gruel and grime of life. But blanket affirmation, affirming someone wherever they are and however they think it is good to proceed forward, is not an inherently good move. In general, black and white affirmation means affirmation in spite of knowing what it is the person is engaging with. Indeed black and white affirmation is part of the mental framework that says there is no singular good towards which to work. It means letting people find their own good in the world, wherever that is and however it might appear. It would be reckless to simply affirm my child whenever they engage in an activity that they would assume to be ‘good.’ At the end of the day, I might not have a house left to live in. As stated previously, though, Postmoderns do not think that it is okay to affirm a murderer. Affirmation requires nuance, attention to that which is good (but we’ll get to that in a second).

Of course, these two loves within Postmoderns do not exist in isolation: they cooperate together. When these two loves work together, they come in and contribute love where the other is deficient, and work together to create a higher experience of love. Delight helps define the limits of good and evil so that affirmation is more effective in community, so that healthy boundaries are found for people and for relationships. Affirmation, as a more abstract experience and expression of love, gives relationships substance even when delight is not to be had. Affirmation itself as an act introduces a level of delight in the one who gives as well as the one who receives, though. In the end, the ideal of love is embodied by these two dimensions of delight and affirmation.

There is, however, a more important form of love. There is a love that is greater than these two, a more ‘noble’ form of love, if you will. In truth I believe it is the type of love that Postmoderns are trying to establish and maintain where they are instead conveying affirmation, or a mix of affirmation and delight.

This more noble form of love is present in delight and outside of delight. This more noble form of love is pure, it expects no good feelings in return. This more noble form of love is entirely focused on the other, and it strengthens others. But, most importantly, this more noble form of love is good. Objectively good. It cannot deviate from good otherwise it is no longer the same love.

The best definition I know of this love is this: to will the good of the other, for the sake of the other. In traditional Catholicism this is called caritas (charity).

We could rephrase it like this: to desire and want objective goodness for someone that is not yourself, for the benefit of this other person and for no other ulterior motive.

Now, this may look like affirmation. When someone else is pursuing something that is good, one affirms them and encourage them to continue on pursuing such a good.

But, and this is the bad news, if someone is pursuing something that is not good, caritas means not affirming. It even means, God forbid, correction.

One can see how, in the Postmodern mindset, this immediately translates to hate. To oppression. If one disagrees with another on the premise of what is good and therefore does not affirm that other person in their choice and identity, then that equates, in the postmodern mindset, to not loving. Even worse, if one even pretends to correct someone, one is talking about about oppressing that person with one’s own views, as that other person likely sees no wrong in how they have chosen their identity and life.

As I have said, caritas is not present within Postmodern thought, as it inherently does not think that there is a singular and ultimate good worth pursuing that does not end up becoming a rule of oppression. One might argue that sacrifice is a key point of liberation, and that caritas does exist within the postmodern mindset, but the sacrifice is not oriented towards objective good – it is oriented towards an inherent lack of objective good. If Postmodernism opens itself up to the idea of objective good, a subject of debate and inevitable ‘oppression,’ then it would defeat itself in argument. Sacrifice? Yes. Caritas? No.

The moment, though, one refers to objective good, an argument of religion is inevitable. Any source of discussion that may arise in the correction of someone LGBTQ+ brings itself back to religion and back to God. The objective is to shift the location of the discussion. Instead of objectively analyzing where Postmodern philosophy or new wave feminism takes a stand, the location shifts to the philosophy and theology of religion (however shallow), attempting to deconstruct the idea of an objective good. First and foremost in the arsenal of retorts is Christ’s own commandment to love one’s neighbor:

“You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it, You shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22:34-40).

“How can you pretend to love God and not love someone that is LGBTQ+? How do you synthesize those two things? Jesus never specified that you should love everyone except LGBTQ+ people.”

The issue, here, is that a Postmodern reads “love your neighbor,” and understands this to mean love on their own terms rather than what religious tradition has taught. It means to not judge, to not hate or oppress. It means to affirm and to delight in them, without desiring them to change.

Remember, though, that caritas is desiring the objective good for others. It’s not about delight, it’s not about blind affirmation, it is about desiring others to pursue good. Even outside of the context of religion and the LGBTQ+ community we see that this is a higher good. If someone has racist views or racist biases, then we should want that person to change, not just for how that person impacts others, but also for improving their own lives and liberating them from such toxic thoughts and ideas. There is good in wanting someone to change for the better, regardless of how that change might return and affect the agent of change themselves.

“So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27).

The Bible only ever makes reference to two genders – male and female. These two sexes. New Testament exhortations are directed at husband and wife, not two wives and not two husbands.

“But sexual immorality and all impurity or covetousness must not even be named among you, as is proper among saints” (Ephesians 5:3).

In Romans 1, St. Paul shows the Romans what sinful lives looked like when people turned away from God:

“Therefore God gave them up in the lusts of their hearts to impurity, to the dishonoring of their bodies among themselves, because they exchanged the truth about God for a lie and worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed for ever! Amen. For this reason God gave them up to dishonorable passions. Their women exchanged natural relations for unnatural, and the men likewise gave up natural relations with women and were consumed with passion for one another, men committing shameless acts with men and receiving in their own persons the due penalty for their error” (Romans 1:24-27)

In all of the years of the existence of the Church, there has never been a hint of support for a sanctified sexual relationship that was not defined as being between one man and one woman, that is inherently open towards the possibility of life.

Ultimately there is no place for someone to practice and/or prioritize a life as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. Why? It prioritizes delight, self-interest, and pleasure over the caritas that we receive from God. The individual prioritizes their chosen identity over the identity which was given to them. God was not afraid to give us morals, to give us a perfect ideal to work towards. One of these ideals is the beauty of sexual relationships. Say what you want, there is only one combination of sexual organs that has the potential to create life. Even if a singular act does not ultimately result in procreation, it had the potential to. No other combination works to make that happen.

Just stop and think about it for the second. We are talking about the ability to create another living human being. Do you know how long science has dreamed of doing that artificially? It is an awesome power, something akin to superpowers (that’s right ladies, I just called you superheroes). By reason alone, and especially informed by Divine authority, we can see that this form of sexual relationship (1 man + 1 woman) is more noble and more correct than any other form. It can inherently produce goodness (more life), even if the act was performed in an evil way.

For this reason the Church says that homosexuality (or other forms of sexual relationships that are not heteronormative, and even masturbation) is intrinsically disordered. It means that these sexual acts go against the design that God has given us, and that they defile the natural beauty of what sex is meant to be.

“It’s God’s fault that He made me this way. Being gay isn’t something I can control, it’s not a choice. If God didn’t want me to be this way, then He shouldn’t have made me gay.”

There are many elements of human nature that we don’t really have a choice over. Our hearts beat without our willpower, neurons fire without our permission, so to speak. We get hungry against our wills. We feel sad, sometimes, without our willpower. Some people are born infertile, some people are born with bodily deformity. Some people are inadvertently affected by drug consumption, and without having any willpower, are more easily addicted to material substances. All human beings, however imperfect, are beautiful children of God. We are born, however, into an imperfect world and we have many affectations that withhold us from the glory that God originally designed us by. What the Church responds, in any of these situations, is that we work through our weaknesses and deficiencies to more conform ourselves to Christ, through the Holy Spirit, for the glory of God. In the case of LGBTQ+ relationships, the Church asks not that they change the very substance of their being, and ‘make themselves straight.’ No, it asks them to set aside their personal desires and delights (to experience sexual pleasure in a specific way) and, in St. Paul’s words:

“Therefore, I urge you, brothers and sisters, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God—this is your true and proper worship. Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is—his good, pleasing and perfect will” (Romans 12:1)

One of the images of the Holy Spirit is that of fire. When we speak about God we talk about the definitive Being that is Truth, Love, and Goodness. He is perfect and without flaw. We, as humans, are full of flaws (that’s right, me too. I’m full of flaws). How can a flawed being even approach God? With much mercy and grace. Most people understand this much, but does that mean that we as humans don’t change? God just takes us up the way that we are and doesn’t worry about changing us?

No!

He calls us to perfection!

“You therefore must be perfect, as your Father in Heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48)

Most people don’t understand the Catholic teaching of purgatory. They think it is extra-biblical knowledge that is simply untrue. But it is rooted in this element of caritas and of God. God is so pure, so good, so true, and so loving that if we choose to come close to Him we have no choice but to be purified, like iron ore that is having its impurities burned and sifted away, so all that is truly good is left to be presented to God. Any time (if we put the analogy of time in a timeless place) in purgatory is time where you are burning away your imperfections and the scars of your imperfections so that you may be presented whole and renewed to God, through Christ.

Here then, once again, the Postmodern reads in and sees hate and oppression. They see God as abusive. He says that He loves but He expects us to be different than “how we were created?” Even if the Postmodern might reject the notion of Hell even existing, they’re happy to be afraid of it, or at least rhetorically ask:

If God is all love, how can He condemn someone to Hell?

God does not want anyone to go to Hell. That is not what He desires for people. Since He is Caritas in its most pure form, He desires to be reconnected with us. But He is also Veritas (Truth). If we choose to live in a way that is not true, then therefore we reject Him. Heaven is the beatific vision, the pure sight of God. Hell is separation from God, the most separated we can possibly be. God does not send people to Hell, people choose to go there. Yet it is even God’s love that makes Hell possible.

God loves us so much, and He desires to have a true relationship with us, which means that we would choose Him. Definitionally, if we have the choice between God or not God, then God has to allow there to be a way for us to not choose Him. There has to be a way that we can reject Him. Hell is that possibility. Hell is anything but evidence against God. It is evidence of God’s caritas and mercy that allows us to choose Him and to choose love.

Love is…caritas. And in lesser forms it can be delight and affirmation.

Sometimes before engaging in discussion with someone, we have to realize that we have very different founding principles about how we view our world. Even if one understands themselves to be wholly correct, they have to comprehend the root thought of the people they are talking with. One of the biggest areas of disrupted conversation is when people are talking about the same concept, in different words, or the same word, but different concepts.

When Christians engage Postmodern thinkers, or when Christians confront their own Postmodern tendencies or flaws, they must realize this inherent difference between the love that is God, and the love that Postmodernism preaches. We must also realize the inherent difference between understanding a founding Truth of the world, rooted in God, versus an open pluralism, and championing of pluralistic societies. Postmodernism yields enough to religion, for now, but soon their will be no room for it. This notion of love, which we thought we all agreed on, is indeed not the same. Let us come to terms with it.